The Geography of Milk & The Future of Dairy Farming

For the last year Janice Chen has been learning about dairy farming. As Dartmouth College’s ’82 Upper Valley Community Impact Fellow, Janice partnered with the Upper Valley Land Trust for her project. UVLT’s President Jeanie McIntyre had been wondering about dairy, and about why milk seemed to have been largely overlooked as a part of the local food movement. Was the hood milk on our grocery store shelves milk from our neighbor’s cows? How could we know? The Geography of Milk project was born.

Janice, a Dartmouth Senior, was ready to find answers for this question. Speaking of her initial interest in the project Janice said, “I was immediately drawn to the challenge of understanding an interwoven and convoluted food system, especially as it related to communities in the Upper Valley. The dairy industry can be considered from an almost infinite set of perspectives, from the historical development of specialized milk production to the contemporary economic consequences of an industry in crisis. It’s fascinating to think about how these different forces coalesce into this landscape we are so familiar with.” We all soon learned that this question was not as easily answered as we might have thought.

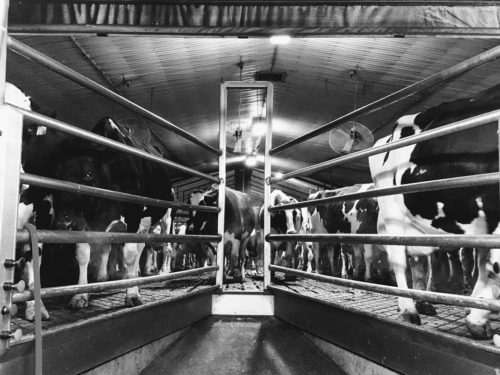

Holding pen at 4am: cows waiting to be milked at a farm in Hamilton, ON.

Janice spent the summer of 2019 working closely with Upper Valley Land Trust staff to speak with dairy farmers and map the farms in UVLT’s 45 town service area. She also ventured into other parts of Vermont, mainly the North East Kingdom, to visit larger farms and see how they operated. She also gained a new appreciation of cows and learned how to milk. “On my holiday break, I went to work on a 500-cow dairy farm in Toronto, ON for five weeks. I woke up at 3am almost every day and milked cows in a parallel parlor until 9am, when the sky was just beginning to light up again. I learned a lot about cows and dairy policy up across the border, which in turn has given me a framework to think about the specificities of dairy farming in the United States.”

6:30am at a farm in Westfield, VT: morning milking almost done.

Along with learning the ropes on the farm and talking to farmers about what their lives are like, what they think of milk production, and where their fluid milk is going once it gets loaded on the truck, Janice started to make maps. She mapped the farm locations first, but then found it difficult to connect the actual farms to processing plants. Where the milk was being shipped could change from day to day depending on plant needs. Instead she turned to retailers to find out where the product on their shelves was coming from. Every fluid milk product has a code on the bottle that, when put into the “Where is my Milk From” database will tell you where the milk was processed.

This can give you some idea of where the milk from is from, but it isn’t always accurate, and depending on how pasteurized your milk is it can be coming from as far away as Utah. So while the maps showed some interesting trends in milk distribution, they lead to more questions than answers.

A cow getting her hoof trimmed

The conclusions of Janice’s report might leave us with more questions than answers. Is milk a “local” food – yes and no. Can we support local dairy farmers with our purchases – yes and no. Are Vermont and New Hampshire losing dairy farms at a quick pace? Yes. As Janice puts it, “The trends certainly suggest that small-scale dairy farming will progressively lose its hold in the Upper Valley. The economic conditions of agriculture right now point to similar results…”

Closing auction at a farm in Morrisville, VT.

So what does it mean? What does the future of dairy in the Upper Valley look like? What will our land use and agricultural landscape look like without iconic dairy farms? Is there anything we can do to mitigate that decline? “…I would hesitate to entirely spell out the demise of dairy farming in the Upper Valley.” Janice said, “I think we also need to ask: what do we want of our working landscape? Is it crucial that we keep it in dairy or in food production at all? Pinning down what is important to us, and why we hold certain hopes for our landscape and food systems will help us think more critically about what will make a sustainable future for this region.”

Randy Robar of Kiss the Cow Farm saying hello to his heifers after morning chores

On February 11th at 6pm Janice will be presenting her research at Dartmouth College, Carson Building, Room 060. Her presentation will be followed by a panel discussion with local agricultural policy experts and dairy farmers, who will try to answer these questions and discuss what they think the future of the dairy industry in the Upper Valley looks like.

This presentation is open to the public and presented by the Upper Valley Land Trust with support from the Dartmouth Center for Social Impact.