Chestnut Hunt Challenge

You just don’t see American Chestnut trees anymore. The once common tree is now all but completely absent from our eastern forests. For centuries they were an essential part of the forest ecosystem and the economy. The trees grew rapidly and tall up to 100 ft. Their late flowering season makes their fruit hardy and unaffected by seasonal frosts. Because the fruit is both hardy and abundant it was an important source of food for wild life and livestock. The wood of the American Chestnut is straight-grained and easily worked. It’s lightweight and rot resistant, making it well suited to many purposes including fence posts, home and barn construction, and fine furniture.

But you don’t see them anymore. In 1904 the first instance of the fungal pathogen Cryphonectria parasitica, known as Chestnut Blight, was discovered in New York. The pathogen had been imported from Asia to the US, likely through Japanese nursery stock, and spread rapidly through the eastern forests. By 1940 most mature American Chestnut trees had been wiped out from the disease.

(Getty Images)

(Getty Images)

The fungus is a quick killer. It enters the tree through damage to the bark and spreads to the underlying layers of tissue, killing them as it moves through. Eventually, the trees have been girdled by the fungus. The tissues no longer serve their purpose of transporting water and nutrients throughout the tree from the roots and the tops of the trees die off. The fungus spread through the air, affecting all nearby chestnuts. The only mature American Chestnut trees left standing were those without another Chestnut within 10km.

These days it’s rare to come across a chestnut tree in the wild but they are not extinct. The species has survived by sending up stump sprouts that grow vigorously in disturbed sites, such as areas that have been logged. Eventually, these too can become infected with blight and die back. Very few trees reach reproductive maturity. But there is still hope for the species. The American Chestnut Foundation is a national non-profit dedicated to the reintroduction of the chestnut tree to its original habitat. They are working to build a better tree, one that can resist the fungus, by creating a hybrid of the Chinese chestnut, which is resistant to the fungus, and the American chestnut.

(Image: Courtesy The American Chestnut Foundation)

(Image: Courtesy The American Chestnut Foundation)

The Upper Valley is at the northern reaches of the American Chestnut tree’s range. We are also at the northern reaches of the fungus’s range. Because of this, there are more healthy, unaffected trees in our area than elsewhere in the nation.

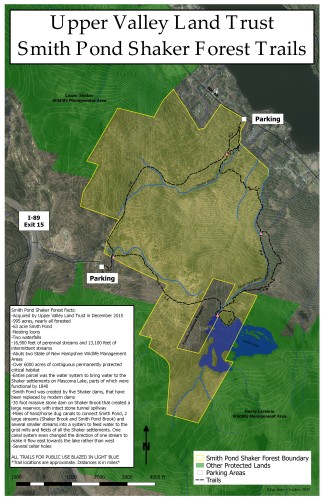

UVLT has found stump sprouts, saplings, seeds, pods, and mature trees at our 995 acre Smith Pond Shaker Forest Conservation Area. We’d like to learn where other Chestnut trees might be on the property and we are challenging you to find them!

Join us on August 28th at the Enfield Public Works Department conference room (74 Lockehaven Road) at 5:30 pm. John Roe, UVLT’s Vice President of Stewardship and Strategic Initiatives will be giving a short presentation about the history of the American Chestnut, both across the eastern United States and here in our region. He will then provide an overview of iNaturalist, the app we are using to collect chestnut tree data and the locations on our property where they have already been found.

Join us on August 28th at the Enfield Public Works Department conference room (74 Lockehaven Road) at 5:30 pm. John Roe, UVLT’s Vice President of Stewardship and Strategic Initiatives will be giving a short presentation about the history of the American Chestnut, both across the eastern United States and here in our region. He will then provide an overview of iNaturalist, the app we are using to collect chestnut tree data and the locations on our property where they have already been found.

After the one-hour presentation we will invite the public to join the Chestnut Challenge! We hope you will visit our Smith Pond Shaker Forest Conservation Area, roam the trails, old logging roads, shaker canals, and remote forested areas searching for American Chestnuts. Do this at your convenience over the next six weeks. When you find Chestnuts, we ask that you document them using the iNaturalist app. The person who documents the most Chestnut observations before October 8th will win the Chestnut Challenge and receive 1st prize, an Octane 8+ Camelback. We will announce the findings of the Chestnut Challenge at our October Open House, held in October.

To view the iNaturalist Smith Pond Shaker Forest project click here.