Celebrating Women’s History Month: Miriam Jarvis Johnson Carreker

Left to right: Miriam Carreker with UVLT’s Peg Merrens

Celebrating Women’s History Month: Miriam Jarvis Johnson Carreker

March is Women’s History Month — and at UVLT, that means it’s time to recognize the many women in conservation who have helped preserve and share the wild spaces in our community.

The Upper Valley has been home to a number of remarkable women conservationists — but Miriam Jarvis Johnson Carreker stands out for her bravery, adventuresome spirit, and vision.

Born in New York City in 1914, Miriam grew up on the campus of Vassar College, where her father was a professor and writer. She was so beloved by Vassar students that the Class of 1922 named her their mascot, though she chose instead to attend the coeducational Syracuse University, graduating in 1936.

From an early age, Miriam yearned to be an active, independent participant in a fast-changing society. After college, she learned to fly while working at an airport — a decision driven by her feeling that she “should like to grow up with the modern world” and her belief that in wartime, “when we need every available man for defense purposes women can play a great part in helping in aviation.” In the early part of World War II, she flew around the country to raise funds for the British Ambulance Corps. In 1943, Miriam enlisted in the Women’s Army Corps, where she served as a lieutenant for three years in the United States, England, and France.

The end of the war brought Miriam home to Schenectady, where she worked at General Electric, became a leader in the League of Women Voters, and met and married her husband Ronald. The couple raised three children before retiring to Hanover, New Hampshire in 1986, where they were active community members involved in educational and environmental causes.

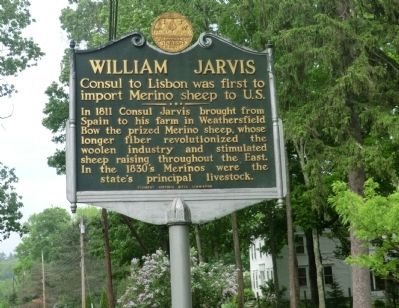

For Miriam, the move was a homecoming of sorts. Generations before, her great-great-grandfather, William Jarvis, had served then-President Thomas Jefferson as Consul to Portugal. He brought back a flock of prized Portuguese merino sheep — and while he gave a few to Jefferson and James Madison, most found their new home in the rocky soil of Weathersfield, Vermont. That decision launched a merino wool industry that thrives in Vermont to this day — and it also shaped the landscape we prize. With the shift to sheep farming, many landowners moved away from timber fencing and instead built the rock walls that have become an iconic sight in New England.

Miriam inherited some of this farmland and knew and cherished its legacy, thanks in part to her mother’s belief in conservation. She noted, “It was my mother who, through the years, managed the property. It was her philosophy that the farm should be kept in use. She felt that it should offer the opportunity for the farmer to profit while following good farming practice.”

In 2004, Miriam ensured that this land would be permanently protected from development by donating a conservation easement to the Upper Valley Land Trust. The 63 acres she protected include prime agricultural soils, a wooded buffer along the Connecticut River, and the land along the historic ferry road that provided a crossing from the Bow to Claremont. At the time, Miriam wrote, “We have all felt, through the years, that it was a small piece of our family history, as well as linked to New England history.”

With her courage and commitment to service, Miriam wrote a new chapter in her family’s history. And though she passed away in 2006, her generous commitment to conservation ensures that it will be remembered for centuries to come.