Connected Habitats for Wildlife

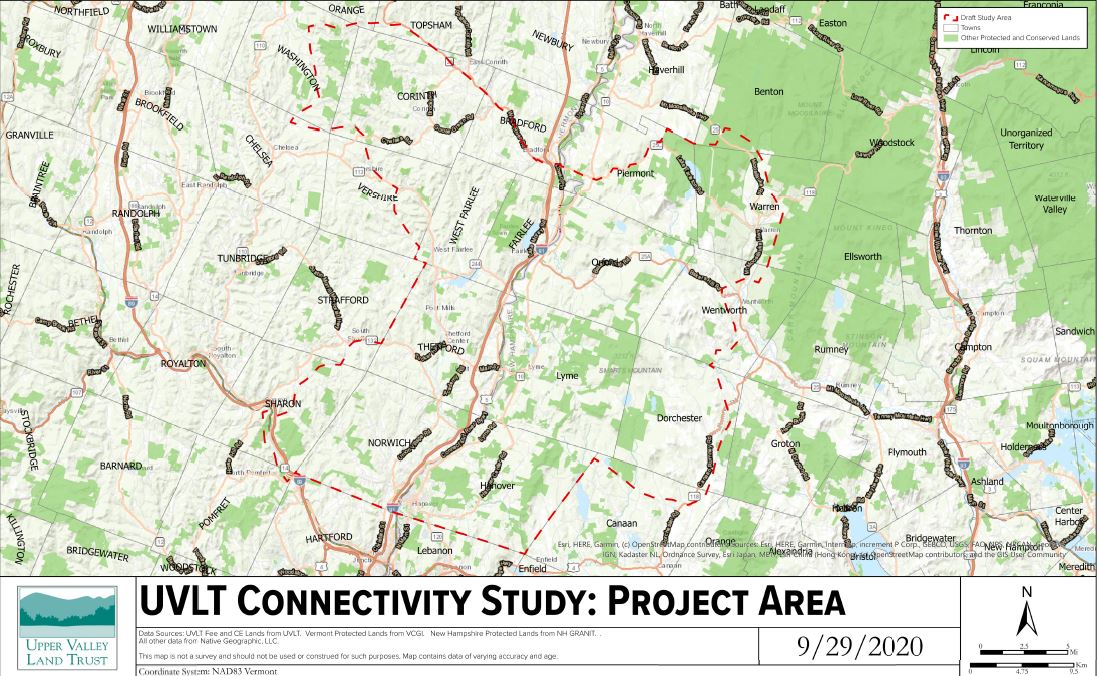

Looking at an area that spans north to south from Haverhill to Enfield and from Corinth to Wentworth, UVLT is using remote sensing and on-the-ground studies to identify opportunities and develop recommendations for protecting, restoring, and promoting ecological wildlife connectivity in the region. Our study of habitat connectivity and wildlife crossings in the northern portion of the Upper Valley began in the winter of 2020 and will continue into 2022.

What is Habitat Connectivity?

Habitat Connectivity is the degree to which the landscape facilitates or impedes animal movement and other ecological processes. Humans have spent centuries shaping the landscape around them and in the process fragmenting it by building houses, roads, fences, utility lines, and other impediments to wildlife movements. These impediments limit access to what was once a large habitat and makes crossing from forest block to forest block more difficult for wildlife. The fracturing of habitat keeps wildlife from reaching food, water, mates, and shelter. Many large mammals need large areas of habitat to roam, and even smaller animals like salamanders, turtles, and frogs, may need to cross roads to move into their breeding habitats.

Why is UVLT undertaking this study?

Protecting wildlife corridors and unfragmented habitat is part of UVLT’s mission. Protecting wildlife habitat means preventing the development of unfragmented wild areas, but it also means creating and protecting areas where wildlife can safely cross already built impediments.

Remote sensing data from both the State of Vermont and the State of New Hampshire provides information about where wildlife corridors may exist in UVLT’s service area. The connectivity study we are undertaking helps to ground truth this remotely gathered data to make sure that the places we believe animals may be crossing roads and using connections are actually where the animals are. If the remotely sensed data is accurate, portions of the Upper Valley are key connections between the White Mountains of New Hampshire and the Green Mountains of Vermont. UVLT is in a unique position to undertake this study as we work in both states and have access to many of the lands in question.

What is a wildlife crossing and habitat blocks? What are you actually looking for?

Most areas where wildlife crossings are successful are areas where there is tree cover or other protective habitat directly up to the road edge. Animals feel safer approaching the road edge and dashing across from one safe habitat to another on the other side. In areas where there is a lot of tree cover on both sides of the road these crossings are called diffuse crossings and they are ideal for wildlife because they can cross at any point on the road more or less safely.

Working with the company Native Geographic, we are evaluating and prioritizing the habitat connections and wildlife crossings that provide direct and functional connectivity between large, unfragmented habitat blocks and core habitat areas.

What have you found so far?

The study began by using a mix of computer based assessments, driving surveys, and winter wildlife tracking to identify, assess, and verify priority habitat connectors and wildlife road crossings as well as other areas of ecological and wildlife connectivity. This spring and summer road crossing surveys were performed and wildlife cameras were installed to survey certain areas where wildlife crossings are suspected. This work is ongoing and will continue through the winter with more winter tracking surveys and camera studies.

UVLT is currently seeking volunteers to assist with this study, particularly to help with game camera management and people who are experienced in winter wildlife tracking. If you’re interested in volunteering for this effort please contact Vice President of Stewardship Jason Berard at Jason.berard@uvlt.org

This study is being underwritten by generous funding from the Lintilhac Foundation and with guidance from our advisory committee: Jens Hawkins-Hilke, Conservation Planner, Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife, Sandra Houghton, Wildlife Diversity Biologist, NH Fish and Game Department, and Conrad Reining.